If you’ve ever stood near an abandoned mine—or even just seen photos of one—you know the feeling. Bare earth. Rust-colored water. A sense that something valuable was taken, and something fragile was left behind. It raises a quiet but uncomfortable question: do we really need to keep digging the Earth deeper to meet our growing demand for metals?

Thank you for reading this post, don’t forget to subscribe!This is where phytomining enters the conversation. Not with loud promises, but with a surprisingly gentle idea: what if plants could help us recover metals instead of excavators?

At first, it sounds almost too poetic to be practical. But once you look closer, the science—and the stories behind it—are far more grounded than you might expect.

So, What Exactly Is Phytomining?

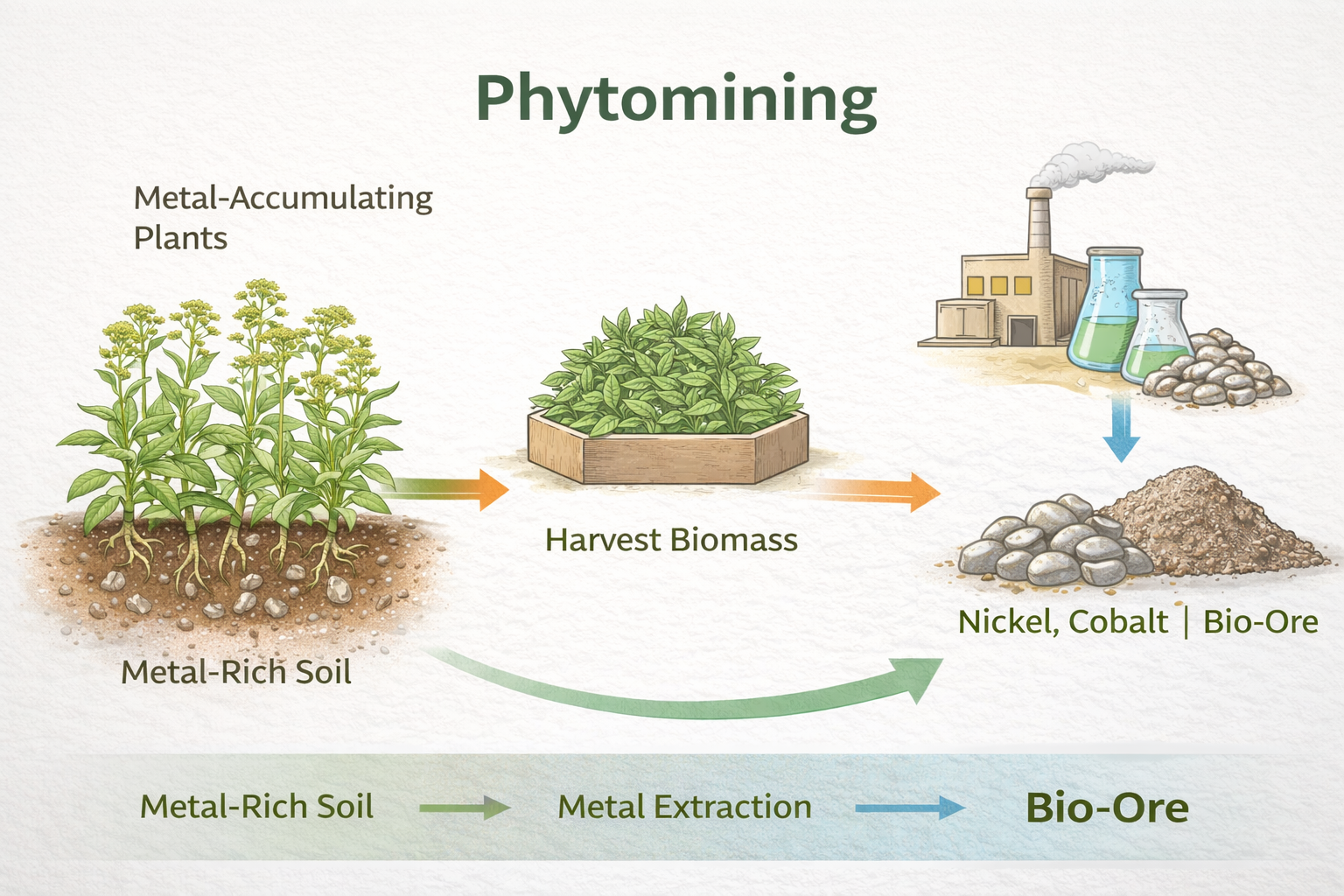

Phytomining is a green technology that uses metal-accumulating plants to extract valuable metals from soil. These plants, often called hyperaccumulators, naturally absorb unusually high concentrations of metals like nickel, cobalt, zinc, or even gold into their tissues.

The process is simple in principle:

plants grow on metal-rich soils → metals move from soil into plant tissues → plants are harvested → metals are recovered from the biomass.

No blasting. No tunnels. Just roots, leaves, and time.

And yes, it sounds slow. But slow isn’t always a weakness.

Why Would We Even Consider Mining with Plants?

Modern life runs on metals. Smartphones, batteries, renewable energy systems—none of them exist without nickel, cobalt, lithium, and rare elements. Traditional mining gives us these resources, but it also leaves behind tailings, toxic dust, acid mine drainage, and long-term ecological scars.

Phytomining offers a different path—especially for low-grade ores and contaminated lands where conventional mining is no longer economical or socially acceptable.

It doesn’t replace mining entirely. But it asks a smarter question:

Can we recover what’s already there, without making the damage worse?

How Do These Plants Do It?

Plants don’t “want” metals. In fact, many metals are toxic to them. But over evolutionary time, some species adapted to survive in metal-rich soils by developing clever internal strategies.

They:

- pull metals into their roots using metal transport proteins

- move them upward through stems

- lock them safely inside vacuoles or bind them to organic compounds

To the plant, it’s a survival trick.

To us, it’s an opportunity.

Species like Alyssum, Berkheya, and Phyllanthus have already shown impressive nickel accumulation in real field conditions.

Real-World Glimpses: Where Phytomining Is Already Working

In parts of Albania, Indonesia, and Malaysia, nickel phytomining has moved beyond theory. Farmers grow nickel-hyperaccumulating plants on ultramafic soils—land once considered agriculturally useless.

After harvest, the biomass is burned under controlled conditions, producing a nickel-rich ash. That ash becomes a raw material, sometimes called bio-ore.

It’s not speculative anymore. It’s happening quietly, locally, and often in places that were left behind by conventional mining.

The Honest Upside—and the Real Limitations

Phytomining has clear strengths:

- it’s low-impact and visually non-destructive

- it can restore value to contaminated or degraded land

- it pairs naturally with phytoremediation, cleaning soil while recovering metals

But it also has limits, and pretending otherwise does no one any favors.

It takes time.

Metal yields per hectare are modest.

Climate, soil chemistry, and plant growth cycles matter a lot.

And it works best for certain metals—not everything.

Phytomining isn’t fast capitalism. It’s patient engineering.

Why Phytomining Feels Different

There’s something quietly hopeful about the idea that plants—often the first victims of pollution—could also be part of the repair.

Phytomining doesn’t shout about innovation. It grows. Season by season. Leaf by leaf.

In a world rushing toward solutions that scale quickly but heal slowly, this approach reminds us that progress doesn’t always need to be violent or loud.

Sometimes, it just needs roots.

A Thought to Leave You With

We often think sustainability means doing less harm. Phytomining nudges us further—it asks whether we can recover value while rebuilding trust with the land.

That’s not just a scientific challenge.

It’s an ethical one.

And maybe that’s why phytomining matters—not because it will replace mining, but because it reshapes how we think about extraction itself.

If plants can adapt to the scars we leave behind, perhaps we can adapt too.

Leave a Reply