-

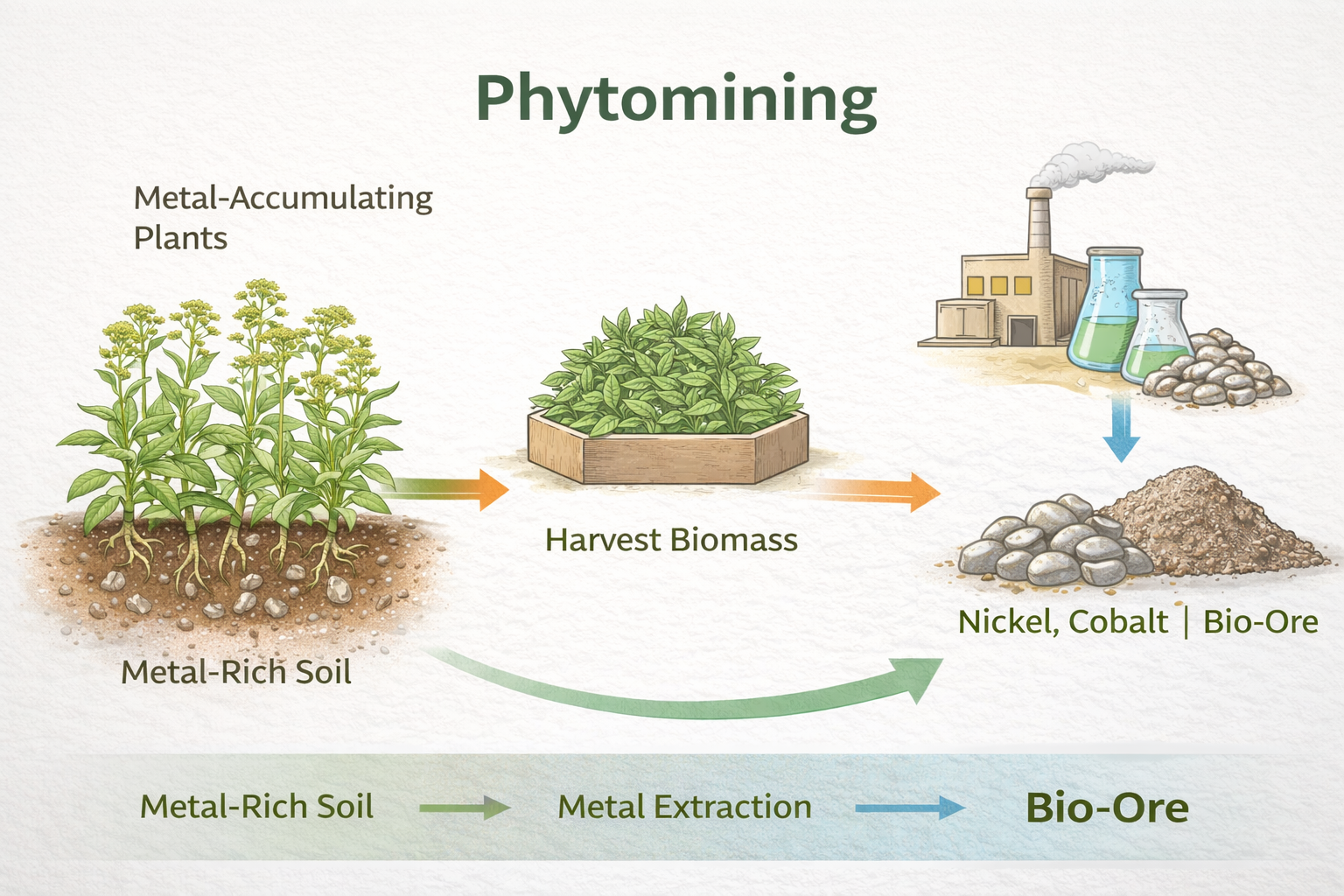

From Research to Practice: Phytoremediation in Wetland Water Treatment

Stand at the edge of a wetland for a moment and watch it closely. Water moves slowly, plants bend and recover, sediments settle, insects skim the surface. This is not a passive landscape. It is a working system, constantly processing what flows through it. For centuries, wetlands have filtered water, stored carbon, and softened floods.…

Written by

-

Can a Lab-Scale Innovation Be Patented? The MVP Dilemma

What founders, researchers, and innovators in biotech and environmental science really need to know A familiar dilemma Imagine this. You’ve built a lab-scale biochip that can detect a single water contaminant in minutes. It works. Early users are excited. A potential collaborator asks a dangerous-sounding question: “Have you patented this yet?” You freeze. It’s not…

Written by

-

From Lab to Land: Why Technology Transfer of Environmental Technologies Matters More Than Ever

Every year, the world produces groundbreaking research on climate change mitigation, clean energy, water purification, waste reduction, and biodiversity conservation. Yet, rivers remain polluted, landfills grow, carbon emissions rise, and communities struggle with water scarcity. The uncomfortable truth is this: innovation alone does not solve environmental problems—deployment does. This is where technology transfer of environmental…

Written by

-

Why does Intellectual Property Awareness Matter for Researchers?

Let’s start with an honest thought Most researchers don’t wake up thinking about patents or copyrights. You’re thinking about experiments, deadlines, publications, and maybe—just maybe—getting one good result after months of work. Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) often feel distant, legal, and irrelevant to “pure” research. But here’s the truth many learn too late:A brilliant idea…

Written by

-

Environmental & Climate Highlights of the Year: What Changed, What Hurt, and What Gave Us Hope

For many of us, this year didn’t begin or end with headlines. It began with sensations.A summer afternoon that felt heavier than usual. A winter morning that arrived late, or barely at all. Rain that didn’t come for weeks—and then arrived all at once, flooding streets, fields, and homes. People remember climate change not through…

Written by

-

10 Eco-Friendly Vacations in India That Won’t Break Your Budget

Have you ever caught yourself scrolling through travel photos and thinking, I want to go somewhere… but without spending a fortune or feeling guilty about my carbon footprint?You’re not alone. More and more travelers are quietly shifting their priorities. Fewer luxury checklists. More meaning. More nature. More local connections. And yes—more affordability.The good news? In…

Written by

-

Why Handmade Holiday Trends Are Stealing Hearts This Season

Have you ever unwrapped a gift and felt a little lump in your throat? Not because it was expensive, but because it felt personal, thoughtful, like someone truly understood you? That’s the magic of handmade gifts — and this holiday season, that magic is winning over shoppers like never before. Let’s dive into why these…

Written by

-

Motorola Edge 70 Review: Premium Design Meets Powerful Performance

The smartphone market in India’s ₹25,000–₹30,000 segment is fiercely competitive, and Motorola has entered the arena with confidence through the Motorola Edge 70. Designed to deliver a premium look, a vibrant display, reliable performance, and long-term software support, the Edge 70 aims to attract both tech enthusiasts and everyday users looking for value without compromise.…

Written by