-

From Research to Practice: Phytoremediation in Wetland Water Treatment

Stand at the edge of a wetland for a moment and watch it closely. Water moves slowly, plants bend and recover, sediments settle, insects skim the surface. This is not a passive landscape. It is a working system, constantly processing what flows through it. For centuries, wetlands have filtered water, stored carbon, and softened floods.…

Written by

-

Horse Latitudes: Meaning, Origin, and Geographic Importance

The Horse Latitudes are one of the most significant and intriguing components of Earth’s global atmospheric circulation system. Known for calm winds, high pressure, and dry climatic conditions, these latitudes have played a crucial role in shaping global climate patterns, desert formation, ocean currents, and historical maritime navigation. This blog explains what Horse Latitudes are,…

Written by

-

Doldrums: Concept, Meaning, Causes, and Importance in Geography

The Doldrums represent one of the most fascinating and climatically significant regions of the Earth. Located near the equator, this zone plays a crucial role in shaping global wind circulation, rainfall patterns, and climate systems. Though often associated with calm winds and oppressive heat, the Doldrums are far more dynamic and influential than commonly perceived.…

Written by

-

From Lab to Land: Why Technology Transfer of Environmental Technologies Matters More Than Ever

Every year, the world produces groundbreaking research on climate change mitigation, clean energy, water purification, waste reduction, and biodiversity conservation. Yet, rivers remain polluted, landfills grow, carbon emissions rise, and communities struggle with water scarcity. The uncomfortable truth is this: innovation alone does not solve environmental problems—deployment does. This is where technology transfer of environmental…

Written by

-

Why Makar Sankranti Matters: History, Culture, Science and Philosophy

Makar Sankranti is one of the most ancient Hindu festivals that celebrates the Sun’s transition (Sankranti) into the zodiac sign of Capricorn (Makara), marking the beginning of the Sun’s northward journey (Uttarayan). Unlike many Hindu festivals which follow a lunar calendar, this festival is based on the solar calendar, falling almost on the same date…

Written by

-

Our Solar System: A Complete, Updated Guide to the Sun, Planets, Moons, Asteroids, and Cosmic Discoveries

Introduction: Our Cosmic Neighbourhood The Solar System is humanity’s first window into the universe—a vast, dynamic system shaped by gravity, time, and cosmic evolution. From the blazing Sun at its centre to icy objects beyond Neptune, the Solar System is home to planets, moons, asteroids, comets, and countless mysteries still unfolding through modern space exploration.…

Written by

-

Mountain Lion: The Silent Ghost of the Wilderness

Introduction Quiet, powerful, and rarely seen, the mountain lion is one of the most mysterious predators on Earth. Known by many names—cougar, puma, panther, or catamount—this majestic big cat has inspired awe, fear, and folklore across the Americas. Despite its wide range, it remains a master of invisibility, often living close to humans without ever…

Written by

-

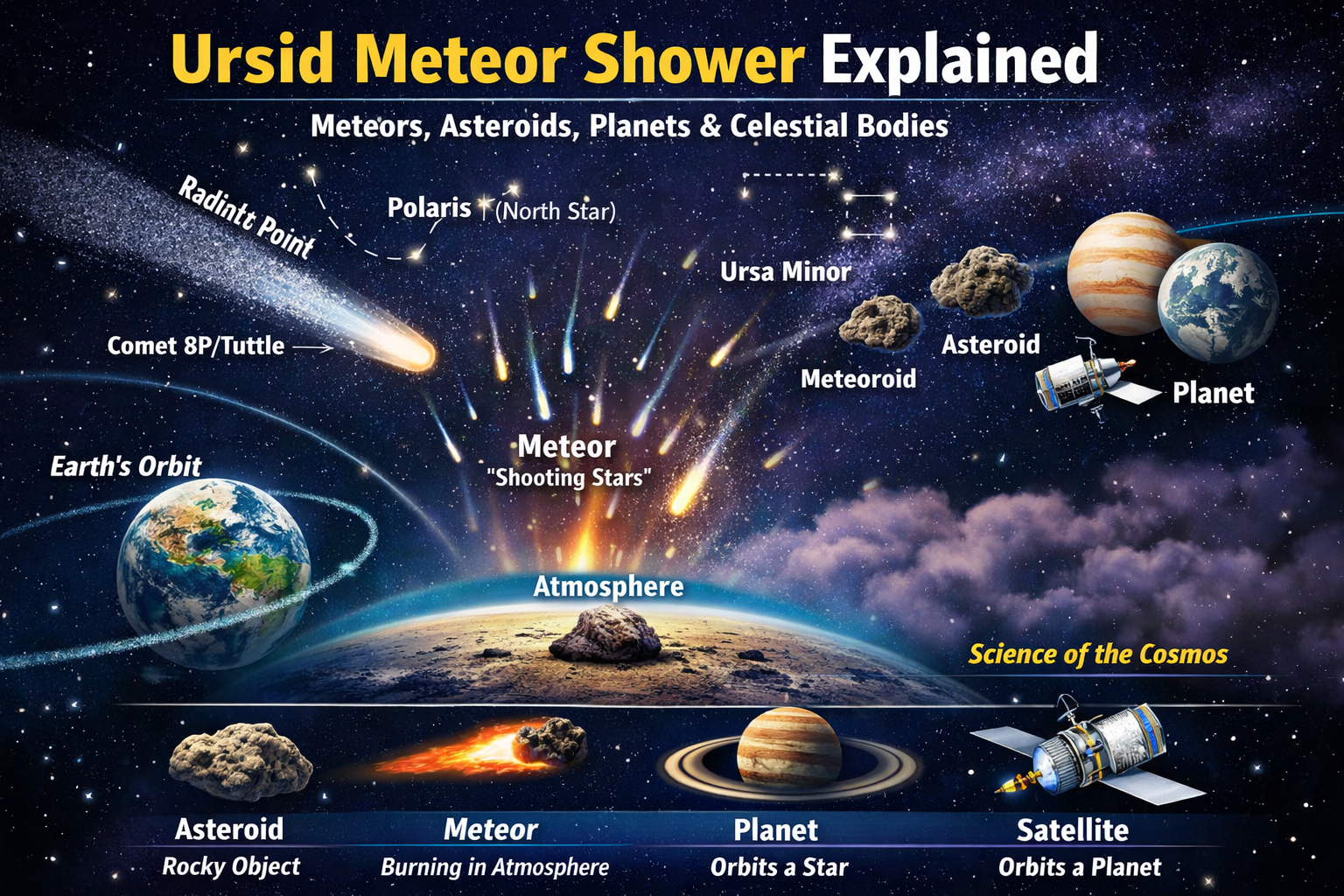

Ursid Meteor Shower: Science, Significance, and the Fascinating World of Meteors

Introduction Every year in December, when winter deepens in the Northern Hemisphere, the night sky offers a subtle yet fascinating celestial display known as the Ursid Meteor Shower. Though less dramatic than the Perseids or Geminids, the Ursids are scientifically important and occasionally surprise skywatchers with sudden outbursts. This blog explains what the Ursid meteor…

Written by

-

Environmental & Climate Highlights of the Year: What Changed, What Hurt, and What Gave Us Hope

For many of us, this year didn’t begin or end with headlines. It began with sensations.A summer afternoon that felt heavier than usual. A winter morning that arrived late, or barely at all. Rain that didn’t come for weeks—and then arrived all at once, flooding streets, fields, and homes. People remember climate change not through…

Written by